I am publishing this blog on December 12, 2012 – a noteworthy date, if only because of its mathematical rarity. This is the last time a date will be defined by three identical, consecutive numbers (12/12/12) for another 89 years (until January 1, 2101, or 1/1/1).

A colleague and I are meeting for lunch today at 12:12 PM, just to add more drama to this (somewhat insignificant) occasion.

Most everyone reading this blog will be gone before the next time this phenomenon strikes. Sorry, that’s just my “prediction.”

Wouldn’t it be nice if all predictions were this easy? Though it’s derived from pure logic, math and scientific data about human lifespan, it’s still only a prediction, because there’s no way to know for sure what will happen over the next 89 years that could change the outcome. But unless medical science changes dramatically this century, my prediction is pretty much a sure bet.

As a pilot, I predict the outcome of each trip by estimating the time of departure and time of arrival. These estimates are derived from several mini-predictors, such as wind direction, wind speed, unforeseen weather (like thunderstorms), miscellaneous Air Traffic Control delays and overall aircraft performance. I have improved my predictions over the years, because with experience, I have become more skilled at analyzing and understanding the impact of each factor.

I think it’s fair to say that real-world business predictors are much trickier to get right. They’re based on complicated trends, which are tied to multiple factors that can greatly alter the outcome. Additionally, there are both subjective and objective factors that come into play. Still, they’re an important part of everyday business management.

In reality, those who predict well have learned how to cheat – meaning they don’t just predict and wait for the outcome. Instead, they adjust their predictions many times along the way as they accumulate new data. In business, not only is this allowed; it’s expected.

Let’s say, for example, that you’re the VP of Sales for a company that provides processing equipment to food manufacturing companies. Part of your job is to make quarterly sales predictions. You estimate sales of $3.5 million for the 3rd quarter, based on the high probability of receiving a $400,000 order from a cereal manufacturer that your team has been working for the last year and a half. You have stayed very close to the progress, and things have continued to look good … until yesterday, when you got a frantic call from the account manager informing you that the client had major fire in their plant. Fortunately, no one was hurt, but the plant will be shut down for at least three weeks.

Obviously, your original prediction will no longer be accurate. The client will need to delay pursuing the contract, or even cancel it altogether.

What if, in the example above, you applied confidence factors to estimate sales? As you move further along the sales cycle, the confidence factor gradually grows from 10 to 80 percent. In this case, you would only have predicted earning $360,000 (80% of $400,000) from this client. Or, if you predicted conservatively at 50 percent, the loss of this client would mean even less of a hit to your sales goals.

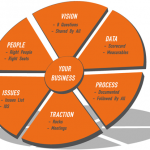

Every company has its unique set of predictors that indicate where they are at any given moment, where they expect to be down the road and, even more importantly, which adjustments might be required along the way. (I touched on this in last week’s blog: “Do You Know Your Number?”)

As your “predictors” become more accurate and timely, you are better able to make the right adjustments to stay focused and on course.

No surprises. Now that’s great management!

11710 Plaza America Drive, Suite 2000 Reston, VA 20190

703.278.CORE (2673)

Leave a Reply